In Please Do Not Step: Loss of a Magnificent Story (2017), Abbas’ fantastical text points to the great tradition of story-telling in the Islamic world (dastangoi), with its sense of loss and legacy. The text is florid and obscure with a multiple of possible readings. References include a flying carpet personified, its possible transformation into an aeroplane and the scattering of migrants around the world’s oceans. The shape of the text block recalls that of a magic carpet zooming into space. The original, temporary, version of this work was commissioned by the V&A Museum, London for the Jameel Prize in 2009 and was made from paper cut out with Islamic geometric patterning: successive viewers eventually obliterated it. The new version is inlaid in marble (from Baluchistan, Pakistan), a technique seen on Mughal architecture, transforming what was a temporary work into a permanent, universalized rendering.

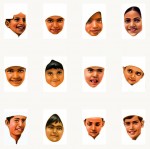

Place.Labour.Capital (2017). In 2015 Abbas was on a research residency at NTU CCA in Singapore. During this time Abbas learnt the courtly Chinese painting style of Gongbi, a ‘meticulous’ and realist painting technique usually executed on raw silk. Originally trained in miniature painting in the Mughal style, Abbas saw many similarities between the two painting styles. Upon her return to Lahore she used the Gongbi technique to paint portraits of the servers, the cooks and the waiting staff, she had interacted with while consuming daily meals at various eateries in the neighbourhood of Little India in Singapore, from her photographic documentation of her encounters. This draws from her earlier series God Grows on Trees (2008) in which she painted portraits of school children taken from her photos of them in Pakistan’s madrasas (religious schools). By appropriating courtly Chinese techniques to tell the story of the movement of Indian laborers, she reveals the exquisiteness of the intertwining of histories, class, race and culture.

Barakah Gifts – Water Bottle (2016) is one from the selection of sculptures based on hybrid objects of daily use collected from gift shops around the two holy mosques. These objects of everyday use are similar to the ones found anywhere else in the world, but incorporates a religious element due to its special context. The artist aim to highlight aspects of material culture in Islam and the commodification of religious desire. Such a bottle is commonly used by the pilgrims to carry the holy water.

Abbas’s Barakah Gifts are large-scale reproductions of commercial souvenirs sold as mementos for pilgrims at the markets adjacent to the two holy mosques. Many of these trinkets find their way back to the pilgrim’s homes or are distributed as gifts for family and friends as blessed gifts. Barakah Gifts II – Penholder (2016) is a colorful composition of shiny minarets, shimmering balls and the Kaaba, transformed into an ostentatious large installation.

Carved from sheesham wood and then painted, these works are hyperrealist sculptures that create icons out of the ordinary. Plastic Flowers I (2016) is an intimate wall-mounted piece taken from a picture the artist took in her mother’s house of a portrait with prayer beads and a stalk of plastic flowers hung over the frame.

Sweet and Savory (2016). The sweet and savory rice placed humbly on the security barrier highlights the current state of unease in Pakistan’s devotional sites and practices: of the coexistence of both hospitality and hostility.

Bodies (2016) is a group of intricately carved wooden footwear taken from photos Abbas had taken outside the entrances to holy sites – a marker of segregation between inside and outside.

In One Rug, Any Colour (2016) Abbas uses a selection of coloured nylon prayer rugs bought by her on Amazon. This work continues the artist’s fascination with colour and of representations of the Kaaba, a throwback to her earlier work ‘Kaaba Picture as a Misprint’ in 2014.

Kaaba Picture as a Misprint (2014), explores how reorienting objects distorts how they are read. The works began by Abbas breaking down the iconic image of the Kaaba into its simplest, yet still recognizable form—two rectangles, one placed atop the other. Abbas broke down each black form into cyan, magenta, and yellow versions of the shape, which were then printed off center. Through this technique, only when the three colors are layered upon each other is the image black. It speaks to the different ways in which religion may be understood and experienced; even when undergoing the same series of events, people may process these happenings in a plethora of ways. By deeming her method a misprint, the artist links the quest for truth and perfection through religious devotion to the capacity for human error.

Justine Ludwig

Kaaba Pop-Ups, initially commissioned for KOCHI-MUZIRIS BIENNALE 2014 was a series of 24 hand-made paper sculptures in various shades of blue intricately folded into Islamic stalactite patterns, which at their centre contain a three-dimensional boxlike space reminiscent of the Kaaba. A miniature artist by training but more famed for her photography and multi-media work, Abbas marks a return with this project to working with paper on a dramatically intricate scale.

Laura Egerton

Wall Hanging, Hamra Abbas’s art installation on the front of the Gardner Museum showed the spectacular silk and gold curtain (kiswa) that covers the door of the Kaaba in Mecca, Islam’s holiest and most venerated site. The artist was inspired by a small plaster cast of this object displayed in her mother’s house in Lahore, Pakistan…

Pieranna Cavalchini

Hamra Abbas was formally trained in the Indo-Persian tradition of miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore. In her practice, Abbas departs from this historic tradition by merging it with contemporary media such as installation and performance.Throughout her career, she has explored the ways in which faith, ritual, and tradition manifest themselves physically. In her series, Kaaba Pictures, Abbas investigates personal and collective expressions of faith surrounding the Kaaba, a black-cloaked, granite cube sacred to Islam. The Kaaba is also at the center of a global consumer industry, which capitalizes on the significance of the site to create thousands of mass-produced objects emblazoned with images of the iconic structure. Fascinated by the many colors and forms of these ubiquitous commodities and the roles they play in private devotion, Abbas began a long process of recreating the fraught trinkets. For the artist, each translation across media reveals new information, and allows for tensions to emerge between public and private devotion, as well as between the idealized image and the everyday experience.

Erin Poor

In Artists series, Abbas looks at the canonized figures of contemporary art. These individuals have taken on a quasi-religious significance in the art world. She begins by working on an intimate scale — sculpting various models of each artist and selects only one to be photographed and printed on a larger-than-life scale. This allows for an act of translation between personal and public.

Justine Ludwig

Idols (2012). Over the years, I have consistently produced work that involves an element of interaction with its place of origin. It is so that I have been taking photographs of people in Cambridge and Boston over the last one year, and in Istanbul more recently, where I was invited to spend some time. During this time, news of economic slowdown, high rates of unemployment and the Occupy Movements have been constantly in focus in the media. This forecast of events seemed to be confirmed by the daily protests taking place across many cities. I began to take note of the quotidian in my immediate environment and took to photography as the most efficient means to do so. I photographed random people while running chores on a daily bases, photographing people working at the supermarkets, post offices, deli stores, restaurants, T stations, construction sites, street vendors, handy-men, and taxi-drivers etc. This gradually turned into a photo journal of the day-to-day. Asking to take their photograph for no reason other than my being an artist animated and displaced the moment, expanded time. In exchanging greetings, and short encounters, I realized how a quick contact and a conversation with a stranger, does entangle or compel us into a web of relationship, and has the potential to transform us. Later on, I started turning each photograph into a tiny sculpture and storing it away in a box. Over a period of time, I had a number of boxes, and hundreds of heads. 22 heads as prints are currently on display. Idols is an ongoing work.

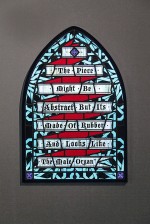

The piece might be abstract, but it is made of rubber and looks like the male organ (2012), is based on the response I received from Pakistan customs after my piece was confiscated. I found the response to be an amusing and yet a revealing one. So I used stained-glass, a medium that is often associated with religious instruction, to mimic the response that stems from the moral imperative to distinguish the good from the bad.

Objects (2012)

Titles (2012) appropriates two titles of 17th C Indian miniatures. The Indian miniature paintings in finely printed catalogues illustrating archives, museums and ethnographic collections often come with titles that attempt to capture the significance of the painting. These titles are mainly determined by curators or scholars, sometimes dealers, to translate oriental art for western understanding. They can often be reductionist, even absurd. In Titles, I reference two titles without the image to provoke an ‘imagining’ to create your own reality. It also plays upon the arbitrariness of the process that is involved in similar attempts of translation.

TextEdit (2011) highlights the climate of fear and surveillance by making edits to an email as it is being written, where the author is sharing her experience of being pregnant. The work attempts to capture the absurdity around this discourse of fear that carries the potential to interpret almost anything as act of suspicion.

Woman in Black (2011). Comprised of three stained glass windows measuring three meters in height, Woman in Black depicts the iconic image of a fictional female super-heroine. To view the work the audience is invited to sit on pew-like benches, inside a darkened room reminiscent of a place of worship. Stained glass, as an art form, reached its height in the middle Ages. Like the illuminated manuscript, it was used to illustrate narratives of the Bible to a largely illiterate populace. Seen from inside a place of worship, such windows were deliberately intended to focus the attention of the worshipper on the sacred image by literally ‘blacking out’ contact with the outside world. The interplay of light and dark have often served as metaphors for good and evil and are deliberately employed by Abbas to accentuate the mysterious powers of the female figure, enshrined within the glass. Shown in the company of an army, brandishing swords, and decapitated fighters, the female figure is shown either under attack or quelling an act of violence. She is placed in the middle of a scene of conflict, suggestive of the worldly realities of contemporary society. Though Abbas uses traditional Indian miniature painting to depict the female figure, stylistic flourishes borne out of the stained glass process intercede. Such quirks register the overlap of traditions and skills within the work. Conceptualizing the belief that the message is found in the medium, a tenet that informs much religious art, Abbas playfully adapts an illuminated painting into an illuminated window, whose image by design, come and goes with the fading of the day. Sharmini Pereira

Su’ar (2011). The word su’ar is used both in Urdu (dialect) and Punjabi for boar. Boar is a repugnant animal in Islam whose meat is forbidden to Muslims. This is seen to be largely in line with all prophets prior to the Prophet Muhammad. The Quran and the tradition (Sunnah) of the Prophet categorically forbid its consumption on the basis that it is impure. Hence it is also used as a pejorative, and if the occasion permits, to be generously used as a hideous insult. As a result of this bias, the boar is seen as a creature that is the filthiest in entire animal kingdom. Due to this view the boar has become an image or motif for shamelessness and depravity of the worst kind. Anyone who is excessively greedy, lacking in hygiene, eats continuously, has no respect for any individual, sexually promiscuous (to the extent of incest) or devoid of any sensitivity may legitimately be called a su’ar. One must add here that it is beside the point if chickens, or for that matter, any other animal may be seen to indulge in the same habits as the boar. Irfan Moeen Khan

Cityscapes 1 (2010) – seemingly an ordinary collection of touristy photographs of Istanbul is made truly ordinary by removing one element that upon first glance generously gives away the city’s character and history. Each shot taken at the crack of dawn is embedded in a narrative that invites the audience to imagine waking up one morning to find the city changed overnight, literally. Since a long time the minarets have been seen as symbols of political Islam in the Western imagination. In the Muslim world, minarets are part of the wider socio-cultural and aesthetic framework, standing above the winding alleys below, as they are, silent spectators to the bustling market places around, listening from the heights the daily conversations of the multitudes scattered on the ground. One may imagine that the minarets of Istanbul are its memory organs that allow the city to recognize itself at each sunrise.

Why do fake hands not clap (2010) consists of a dozen sets of the artist’s hands (plaster casts) in clapping motion, and disintegrating as a result. In the video, the clapping produce an eerie soundtrack to represent the destructive impulses cloaked in our collective approval. The sound is not one of applause, and yet it is created by the very act of applause. So it is this disconnect that produces the anxiety, and plunges the viewer in a landscape of broken shards falling all around.

Love Yourself (2009) is an installation of vibrating, toylike fighter jets, missiles, bombs, and bullets that when switched on together with the neon works on the wall, create a vibrant installation of sound, movement, and light. The background neon reminds us that it’s “as good as the real thing”. The installation seeks to draw the attention of the viewer by a titillating display of colorful vibrating objects and blatant sexual innuendo—voyeurism giving way to a disturbing realization that these symbols of violence have been turned into pleasure objects.

video documentation by Kent Long

Paradise Bath (2009) is a set of 9 photographs, and an outcome of a performance I did during my visit to Thessaloniki, Greece. I was immediately drawn to the first Ottoman bath-house built there in 1444. Known as Bey Hammam or Paradise Bath, it stands in the city center as one of the main tourist destinations, as well as a symbol of the country’s Muslim past. This work takes the archetypal Orientalist image of a bath-scene to highlight issues of race, memory and power while referencing the ritual of washing/cleansing — symbolic in Islam and associated with regaining purity.

Please do not step: Loss of a magnificent story (2009) is a site-specific work for Victoria and Albert Museum, London. In this work I use the method of storytelling (dastangoi) to tell a tale of loss and legacy, interlaced with elements of satire and humour. Borrowing from the idea of storytelling, Please do not step weaves together narratives within narratives.

In this is a sign for those who reflect (2009) is inspired by my attendances at meditation sessions in Pakistan. Also called zikr, these were primarily meditations of a Sufi tradition. The movement of the walls, with the sounds of breathing, recorded at these sessions, can be read or misread as an enclosing experience. My interest however, is to recreate elements of a sensory experience to imagine the power of synchronizing to one idea or belief. video documentation

Ride 2 (2008) is based on a mythical animal called Buraq, traditionally the Holy Prophet Mohammad’s ride that carried him from Mecca to Jerusalem and back on the event of Mi’raj in the 7th century. The image of Buraq has an iconic value in the popular culture of Pakistan, often seen painted on trucks, and portrayed as a winged horse with the head of a woman.

God Grows on Trees (2008) consists of 99 individual portraits of children and a C-print. The portraits of the children were painted over a year and informed by my visits to Madrassahs (religious schools) in Pakistan. Viewing the current fascination with Madrassahs as being akin to the orientalist painters’ fascination in the 19th and early 20th centuries with the harem, I attempt to thwart these exoticised readings to portray the universality of childhood experience. In painting the portraits I attempt to reproduce the faces as faithfully as I could, marrying realism with the techniques of miniature. The digital print was added to the work later. This is a photograph of trees along a road in Lahore, that are nailed with metal plates which reproduce the 99 names or attributes of God in Islamic tradition, and in fact gave the work its title as well.

In Please do not step 2 (2008) Hamra Abbas uses thin interlacing strips of paper to form the Arabian stalactite work that has been stuck to the floor of the gallery. This dramatic and at the same time delicate and ephemeral work is around 30 meters long and crosses the natural path followed by visitors to the exhibition. In the form of a text, it traces out clear message, despite its size, whispers ‘Please do not step”. Enrique Martinez

Abbas works in many different media, inventing, intriguing, and critical, ways to comment on conventional ideas. In Paper Plates (2008), her target is the ‘skewed dynamics of cultural consumption’. Thin strips of paper have been printed with the phrase, ‘Please get served’, endlessly repeated. Discs of paper collage were made by combining the strips in complex geometrical patterns, which are recognisably Islamic. The discs were then hot-pressed into paper plates, a part of everyday life in every continent. The plates, though, are full of holes and cannot be used to ‘get served’. Tim Stanley